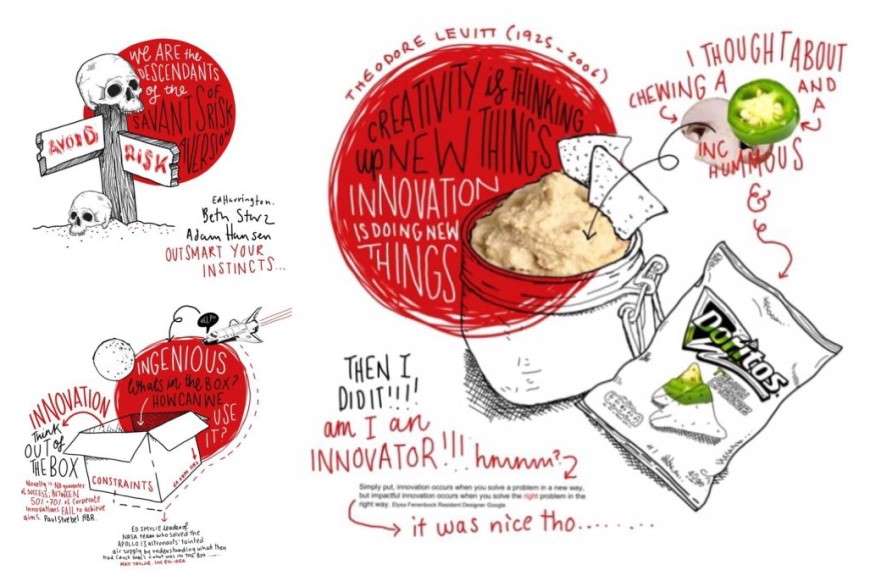

Picture credit: Tash Willcocks, Hyper Island

Picture credit: Tash Willcocks, Hyper Island

I’ve just come back from the IRM Innovation, Business Change and Technology conference, where we were exhibiting, and I am a broken woman.

Three days of workshops, presentations, conversations, and networking in air conditioned rooms means my head is full of information, my bag is full of business cards, and I don’t feel like leaving the house again for a week.

But. It’s been an absolutely fascinating three days. I love events where I get an insight into a whole new area of work (I normally end up deciding to change careers and become whatever the new area is for a while before coming to my senses) and this was definitely one of those. Surrounded by change consultants, business analysts and enterprise architects, I had some brilliant conversations and met a lot of lovely people, including David Beckham. No, not that one.

So why the focus on the word failure? Well, what struck me strongly during the event was the clash of language, style and culture that came from sticking Innovation together with Business Change and Technology. Of course, innovation almost always involves change, so the combination makes sense – but it’s still a long way from the front end of innovation, where it’s all about fuzzy ideation and experimentation, to the implementation bit where you try to create value from change.

In my talk, I discussed how almost every interviewee in Innovation Conversations had said that innovation is painful, difficult and littered with failure. And failure came up in a number of other presentations, including a great session from Tash Willcocks of Hyper Island. But after an excellent question from the floor about failure, I started to reflect on the fact that what I (and my interviewees) meant by failure might not be what the conference audience associated with the word.

(This made Steve Whitla’s presentation on using language to create shared meaning incredibly relevant at this point – perfect serendipity.)

For me, embracing failure is about two things. First, trying multiple things in the full and certain knowledge that some of them won’t work, but you don’t know which ones. That’s the point of experiments. If you already know which ones will work, then there’s no point experimenting. Ideally, you run enough experiments simultaneously to find one that works beautifully, or maybe two that work, and then you scale up. At this point, the failure of the ones that didn’t work doesn’t matter, because you’ve found a way forward and you didn’t spend much on each one.

But if you only try one thing, whether as a pilot or as a full blown business transformation programme, then you’re saying that you’re reasonably confident that this one will work, and if it fails, then of course it is a big deal. You have to write off the costs and start again from scratch, and management teams don’t like to hear that message much. So it’s not surprising that the word failure makes people working on big, expensive transformation and change programmes uncomfortable.

Second, we know that large organisations are generally risk averse, and while that’s a normal product of their scale, it creates a culture in which people are scared to experiment. In a risk averse culture, people will only try something if there’s a high chance of success, because the consequences of failure are too huge and dire to contemplate. So the other reason to embrace failure publicly is in order to send a message to the organisation that it’s ok to fail, particularly while experimenting at small scale, as long as there is learning from failure.

Of course, the word failure makes people sit up and listen, and that’s partly why so many people are using it right now. But it’s become a sledgehammer to crack a highly nuanced nut, so I think we need to stop hammering it now. For me, a more sensible message is this:

- Build experimentation into the early part of your projects, to avoid failure turning up unexpectedly at the end.

- And use robust insight and analysis to come up with a few different options for experiments.

Adrian Reed’s session on systems thinking (you can see a webinar recording of a similar session on his website) demonstrated beautifully that with complex problems there are always multiple variables on which you could experiment, to see which one is most effective – or even that you could tackle the same variable with some different approaches.

Of course, there are going to be times where this isn’t possible. There’s never a one-size-fits-all approach to solving problems, and David Beckham’s presentation about change reinforced that sweeping, unilateral changes of approach (‘we will now all be agile’) are often going to be diluted and evolved as they bed down.

So that’s all I have to say about failure. Having left the stage after my presentation kicking myself for all the things I left out or didn’t explain properly, I’m going to embrace my failure to get those bits right, and learn for next time. And then I'm going to stop using the f-word.